Another word added: harridan: a strict, bossy, or belligerent old woman

I have two new words to add, one that has been in the news a lot recently (early March 2012) when Rush Limbaugh called Sandra Fluke (a young woman who testified before Congress on birth control) a "slut." The definition? According to Urban Dictionary, a slut is someone who "sleeps with everyone, even the guy that has not shot at getting laid and everyone knows it."

Another term that recently came to mind is battle-axe, defined as "a very aggressive and bad tempered old woman.

My point with these definitions and those that follow is that there are no comparable words for males.

There are many terms that have gone out of use in these politically-correct times. But we dare not forget them. I like to think of myself as a good old-fashioned housewife--maybe even a hussy, as a housewife came to be known, especially an outspoken independent sassy scold. (We'll deal with the term scold further on.)

But the term housewife is a good place to start.

QUESTION: I've heard the origin of hussy is simply housewife. Was housewife commonly pronounced as "hussy", or is that more a colloquial thing? When did it take on the negative connotations it has today?

ANSWER: Yes, you are correct, it is a contraction of housewife. It dates in writing from the 16th century. Originally it simply meant "housewife" or "mistress of the household". However, it soon also had the meaning "thrifty woman". In 1722, we find, "Her being so good a hussy of what money I had left her" from Daniel DeFoe's The History and Remarkable Life of the Truly Honourable Colonel Jacque.

ANSWER: Yes, you are correct, it is a contraction of housewife. It dates in writing from the 16th century. Originally it simply meant "housewife" or "mistress of the household". However, it soon also had the meaning "thrifty woman". In 1722, we find, "Her being so good a hussy of what money I had left her" from Daniel DeFoe's The History and Remarkable Life of the Truly Honourable Colonel Jacque.

By the middle of the 17th century, the word hussy took on negative connotations and was used to refer to women in a rustic or rude manner. For example, in Thomas Hobbes' translation of Homer's The Iliad (1677), Hobbes wrote, "Then Venus vext, 'Hussie!' said she, 'no more Provoke my anger.'"

Around that same time, in rural dialects, the word came simply to mean "woman", and then, as country women were thought rough and rude by their more genteel counterparts in the cities, it came to refer to a badly behaved or mischievous woman, and even a lewd or wanton woman. This change in meaning had occurred by the 18th century.

http://www.takeourword.com/TOW205/page2.html

FISHWIFE

FISHWIFE

This is another old English term, pronounced: fish-wayf. Noun

Meaning: No, even if you married a cold fish, you are not a fishwife. You are, however, if you are 1. a woman who sells fish or 2. a woman who uses coarse, vulgar language.

Back in the days of Billingsgate, women who sold fish acquired the reputation of using abusive language. I suppose smelling fish all day could have that effect on a woman. In fact, women who sell fish are not called fishwives anymore but the reputation of their name carries forward: "When I told her that her son would be working for mine someday, she turned and left, swearing like a fishwife."

Word History: The historical question raised by this Good Word is, why did female fish-peddlars have to be married? In fact, they didn't. In Old English, wif meant simply "woman". Woman, in fact, derives from Old English wifman "a woman person" (as opposed to a wæpen-man "weapon person" = a man). So, the original meaning of fishwife was simply "fish woman".

http://www.alphadictionary.com/goodword/word/fishwife

Old wives' tale

The Gazette (Colorado Springs), Dec 27, 2004 by Deb Acord

Betty started it.

Friedan, that is. With her book, "The Feminine Mystique," published in 1963, Friedan urged a generation of women to see that there is more to life than housework.

The suburban housewife, Friedan wrote, "was the dream image of the young American woman... She was healthy, beautiful, educated, concerned only about her husband, her children, her home."

The suburban housewife, Friedan wrote, "was the dream image of the young American woman... She was healthy, beautiful, educated, concerned only about her husband, her children, her home."

But as women lived the dream, Friedan wrote, they were taunted by what she called "the silent question": "Is this all?"

Housewives are back in the American consciousness, thanks in part to a hit TV show. But this time, they're not content to stay at home dusting the dining room table. In the ABC drama, "Desperate Housewives," they're portrayed as beautiful, sinful and secretive. In an upcoming pictorial feature in Playboy magazine, housewives will be portrayed as sexy. In real life, they're still proud of their homes, but jobs, volunteering and other activities cut into their dusting time.

Friedan's book started a revolution and still is considered a cultural icon. Writer Anna Quindlen said it changed her life. In the introduction to a 2001 reprint of "The Feminine Mystique," Quindlen wrote, "it changed the lives of millions upon millions of... women who jettisoned empty hours of endless housework and found work, and meaning, outside of raising their children and feeding their husbands."

http://calbears.findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qn4191/is_20041227/ai_n10043353

SHREW

shrew (shrū), noun

1. Any of various small, chiefly insectivorous mammals of the family Soricidae, resembling a mouse but having a long pointed snout and small eyes and ears. Also called shrewmouse.

2. A woman with a violent, scolding, or nagging temperament; a scold.

Shakespeare's The Taming of the Shrew (starring Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton)

CRONE

CRONE

crone n. An ugly, withered old woman; a hag. [Middle English, from Old North French carogne , carrion, cantankerous woman, from Vulgar Latin.

BITCH

BITCH

bitch n. A female canine animal, especially a dog. Offensive. A woman considered to be spiteful or overbearing.

SCOLD

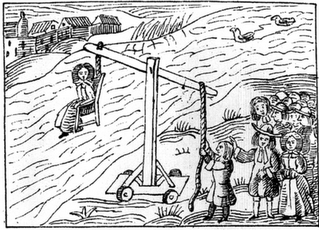

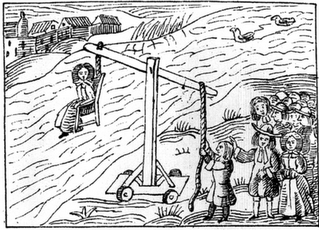

In the common law of crime in England a common scold was a species of public nuisance - a troublesome and angry woman who broke the public peace by habitually arguing and quarrelling with her neighbours. The Latin name for the offender, communis rixatrix appears in the feminine gender, and makes it clear that only women could commit this crime.

This is what you do with a scold. You dunk her in the river.

Hey, it actually looks kind of fun!

NAG, noun and verb

1. someone (especially a woman) who annoys people by constantly finding fault

Synonyms: scold, scolder, nagger, common scold

2. nag - an old or over-worked horse

Synonyms: hack, jade, plug

verb nag - bother persistently with trivial complaints; "She nags her husband all day long"

Synonyms: peck, hen-peck

Nag: (năg), n. 1. A small horse; a pony; hence, any horse, especially one that is of inferior breeding or useless.

2. A paramour; -- in contempt. Shak.

Nag: to scold habitually; to annoy; to fret pertinaciously. “She never nagged.” J. Ingelow.

From the Writing of Ray Stedamn

I heard of a man who called his wife Peg although she really had another name. Someone asked him why he did this and he said, "Well, Peg is a short for Pegasus, and Pegasus was an immortal horse, and an immortal horse is an everlasting nag so that's why I call my wife Peg!"

I heard of a man who called his wife Peg although she really had another name. Someone asked him why he did this and he said, "Well, Peg is a short for Pegasus, and Pegasus was an immortal horse, and an immortal horse is an everlasting nag so that's why I call my wife Peg!"

What is nagging, anyway? Analyze it, and it is seen frequently to be a subtle evasion on the part of the wife of her responsibility to submit to her husband.

http://www.raystedman.org/moralcon/0081.html

TERMAGANT

ter·ma·gant (tûr'mə-gənt)

n.

A quarrelsome, scolding woman; a shrew.

adj.

Shrewish; scolding.

Old Hag Syndrome

Old Hag Syndrome

"Old Hag Syndrome" sometimes referred to as "Night Hag" is another commonly used term for SLEEP PARALYSIS among many different cultures mainly in the western world. The term Old Hag is probably derived from a couple of sources, one being the word for Nightmare; Night -of course, we know this already, Mare being derived from the old English term Maere meaning demon or incubus (an incubus is believed to be a demon that visits during the night). Other sources as listed by Dr. J. A. Cheyne, University of Waterloo Psych. Dept include German mar/mare, nachtmahr, Hexendrücken (witch pressing), Alpdruck (efl pressure), Czech muera, Polish zmora, Russian Kikimora, French cauchmar (trampling ogre), Greek ephialtes (one who leaps upon) and mora (the night "mare" or monster, ogre, spirit, etc.), Roman incubus (one who presses or crushes) ge, (evil spirit or the night-mare--also hegge, haegtesse, haehtisse, haegte); Old Norse mara, Old Irish mar/more.

Here is an old hag--or a stylish young woman--depending on how your eyes catch the visual representation. Word is, if you stare at it long enouch before you retire at night you'll wake in the night with a case of "Old Hag Syndrome."

Here is an old hag--or a stylish young woman--depending on how your eyes catch the visual representation. Word is, if you stare at it long enouch before you retire at night you'll wake in the night with a case of "Old Hag Syndrome."

DIARY OF A MAD HOUSEWIFE

Made into a major motion picture that garnered an Oscar nomination, Diary of a Mad Housewife is a classic of women’s fiction that gave a wry voice to the nascent feminist stirrings of the 1960s and helped incite a revolution in the consciousness of a generation. After many years, this best-selling novel of Manhattan ennui is finally back in print.

Made into a major motion picture that garnered an Oscar nomination, Diary of a Mad Housewife is a classic of women’s fiction that gave a wry voice to the nascent feminist stirrings of the 1960s and helped incite a revolution in the consciousness of a generation. After many years, this best-selling novel of Manhattan ennui is finally back in print.

When Bettina Balser begins to suspect that she is going mad, she starts a secret diary as a form of therapy and escape. Her fears pour onto the page: "Elevators, subways, bridges, tunnels, high places, low places, tightly enclosed spaces, boats, cars, planes, trains, crowds...." Through her observations of herself and those around her, Bettina seeks meaning in her exceedingly dreary life. Her frank examinations lead to many changes, including an extramarital fling, and her voice touches a timeless nerve, resonating on many levels— from the ever-evolving feminist consciousness to the gnawing existential search that is universal.

Diary of a Mad Housewife’s humor and insight are as alive and pertinent today as they were yesterday, and will charm and disarm men and women of any generation.

"Diatribe of a Mad Housewife" is the tenth episode of The Simpsons' fifteenth season, first aired on January 25, 2004.

Merry Wives and Others: A History of Domestic Humor Writing

by Penelope Fritzer, Bartholomew Bland

In many ways, the history of domestic humor writing is also a history of domestic life in the twentieth century. For many years, domestic humor was written primarily by females; significant contributions from male writers began as times and family structures changed. It remains timeless because of its basis on the relationships between husbands and wives, parents and children, houses and inhabitants, pets and their owners, chores and their doers, and neighbors.

This work is a historical and literary survey of humorists who wrote about home. It begins with a chapter on the social context of and attitudes toward traditional domestic roles and housewives. The following chapters, beginning with the 1920s and continuing through today, cover the different time periods and the foremost American domestic humorists, and the humor written by surrogate parents, grown children about their childhood families, husbands, and Canadian and English writers. Also covered are the differences among various writers toward traditional domestic roles—some, like Erma Bombeck and Judith Viorst, embraced them, while others, like Caryl Kristenson and Marilyn Kentz, resisted them. Common themes, such as the isolation and competitiveness of housework, home as an idealized metaphysical goal and ongoing physical challenge, and the urban, suburban, and rural life, are also explored.

About the Author

Penelope Fritzer is an associate professor at Florida Atlantic University’s Davie campus. She lives in Coral Springs. Bartholomew Bland is the director of exhibitions at the Staten Island Institute of Arts and Sciences. He lives in New York City.

HOUSEWIFE HUMORIST

Erma Bombeck

Erma Bombeck

Erma Bombeck (1927-1996) was born in Dayton, Ohio, USA. When she was nine, her childhood home including all of the furnishings and furniture was repossessed by the bank after her father, a crane-operator, died of a stroke. To survive, Erma developed a wise-cracking, comic approach to life. At 13, she wrote her first humor column for her school newspaper.

At the age of 20 she was diagnosed with polycistic kidney disease, a hereditary disorder which causes cysts to form on the kidneys. Told that she would one day suffer kidney failure, she went on with her life—marrying, having three children, and a career as one of America’s favorite humorists.

Her column, “At Wits End,” debuted in the Kettering-Oakwood Times in 1964. She soon had a huge following in housewives around Ohio. As news of the column spread, it became a nationally syndicated column in 1965, running twice weekly in some 500 newspapers. In 1971, the family and moved to Arizona, where for three decades she wrote about being a mother, wife, journalist, and woman. Her two best known books are The Grass is Always Greener Over the Septic Tank (1976) and If Life is a Bowl of Cherries, What am I Doing in the Pits? (1978).

During the course of her career, Bombeck published more than four thousand syndicated columns in 900 papers nationwide, wrote 15 best-selling books, and became one of the world's most beloved humorist columns. She died of complications from a kidney transplant in 1996.

I have two new words to add, one that has been in the news a lot recently (early March 2012) when Rush Limbaugh called Sandra Fluke (a young woman who testified before Congress on birth control) a "slut." The definition? According to Urban Dictionary, a slut is someone who "sleeps with everyone, even the guy that has not shot at getting laid and everyone knows it."

Another term that recently came to mind is battle-axe, defined as "a very aggressive and bad tempered old woman.

My point with these definitions and those that follow is that there are no comparable words for males.

There are many terms that have gone out of use in these politically-correct times. But we dare not forget them. I like to think of myself as a good old-fashioned housewife--maybe even a hussy, as a housewife came to be known, especially an outspoken independent sassy scold. (We'll deal with the term scold further on.)

But the term housewife is a good place to start.

QUESTION: I've heard the origin of hussy is simply housewife. Was housewife commonly pronounced as "hussy", or is that more a colloquial thing? When did it take on the negative connotations it has today?

ANSWER: Yes, you are correct, it is a contraction of housewife. It dates in writing from the 16th century. Originally it simply meant "housewife" or "mistress of the household". However, it soon also had the meaning "thrifty woman". In 1722, we find, "Her being so good a hussy of what money I had left her" from Daniel DeFoe's The History and Remarkable Life of the Truly Honourable Colonel Jacque.

ANSWER: Yes, you are correct, it is a contraction of housewife. It dates in writing from the 16th century. Originally it simply meant "housewife" or "mistress of the household". However, it soon also had the meaning "thrifty woman". In 1722, we find, "Her being so good a hussy of what money I had left her" from Daniel DeFoe's The History and Remarkable Life of the Truly Honourable Colonel Jacque.By the middle of the 17th century, the word hussy took on negative connotations and was used to refer to women in a rustic or rude manner. For example, in Thomas Hobbes' translation of Homer's The Iliad (1677), Hobbes wrote, "Then Venus vext, 'Hussie!' said she, 'no more Provoke my anger.'"

Around that same time, in rural dialects, the word came simply to mean "woman", and then, as country women were thought rough and rude by their more genteel counterparts in the cities, it came to refer to a badly behaved or mischievous woman, and even a lewd or wanton woman. This change in meaning had occurred by the 18th century.

http://www.takeourword.com/TOW205/page2.html

FISHWIFE

FISHWIFEThis is another old English term, pronounced: fish-wayf. Noun

Meaning: No, even if you married a cold fish, you are not a fishwife. You are, however, if you are 1. a woman who sells fish or 2. a woman who uses coarse, vulgar language.

Back in the days of Billingsgate, women who sold fish acquired the reputation of using abusive language. I suppose smelling fish all day could have that effect on a woman. In fact, women who sell fish are not called fishwives anymore but the reputation of their name carries forward: "When I told her that her son would be working for mine someday, she turned and left, swearing like a fishwife."

Word History: The historical question raised by this Good Word is, why did female fish-peddlars have to be married? In fact, they didn't. In Old English, wif meant simply "woman". Woman, in fact, derives from Old English wifman "a woman person" (as opposed to a wæpen-man "weapon person" = a man). So, the original meaning of fishwife was simply "fish woman".

http://www.alphadictionary.com/goodword/word/fishwife

Old wives' tale

The Gazette (Colorado Springs), Dec 27, 2004 by Deb Acord

Betty started it.

Friedan, that is. With her book, "The Feminine Mystique," published in 1963, Friedan urged a generation of women to see that there is more to life than housework.

The suburban housewife, Friedan wrote, "was the dream image of the young American woman... She was healthy, beautiful, educated, concerned only about her husband, her children, her home."

The suburban housewife, Friedan wrote, "was the dream image of the young American woman... She was healthy, beautiful, educated, concerned only about her husband, her children, her home."But as women lived the dream, Friedan wrote, they were taunted by what she called "the silent question": "Is this all?"

Housewives are back in the American consciousness, thanks in part to a hit TV show. But this time, they're not content to stay at home dusting the dining room table. In the ABC drama, "Desperate Housewives," they're portrayed as beautiful, sinful and secretive. In an upcoming pictorial feature in Playboy magazine, housewives will be portrayed as sexy. In real life, they're still proud of their homes, but jobs, volunteering and other activities cut into their dusting time.

Friedan's book started a revolution and still is considered a cultural icon. Writer Anna Quindlen said it changed her life. In the introduction to a 2001 reprint of "The Feminine Mystique," Quindlen wrote, "it changed the lives of millions upon millions of... women who jettisoned empty hours of endless housework and found work, and meaning, outside of raising their children and feeding their husbands."

http://calbears.findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qn4191/is_20041227/ai_n10043353

SHREW

shrew (shrū), noun

1. Any of various small, chiefly insectivorous mammals of the family Soricidae, resembling a mouse but having a long pointed snout and small eyes and ears. Also called shrewmouse.

2. A woman with a violent, scolding, or nagging temperament; a scold.

Shakespeare's The Taming of the Shrew (starring Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton)

CRONE

CRONEcrone n. An ugly, withered old woman; a hag. [Middle English, from Old North French carogne , carrion, cantankerous woman, from Vulgar Latin.

BITCH

BITCHbitch n. A female canine animal, especially a dog. Offensive. A woman considered to be spiteful or overbearing.

SCOLD

In the common law of crime in England a common scold was a species of public nuisance - a troublesome and angry woman who broke the public peace by habitually arguing and quarrelling with her neighbours. The Latin name for the offender, communis rixatrix appears in the feminine gender, and makes it clear that only women could commit this crime.

This is what you do with a scold. You dunk her in the river.

Hey, it actually looks kind of fun!

NAG, noun and verb

1. someone (especially a woman) who annoys people by constantly finding fault

Synonyms: scold, scolder, nagger, common scold

2. nag - an old or over-worked horse

Synonyms: hack, jade, plug

verb nag - bother persistently with trivial complaints; "She nags her husband all day long"

Synonyms: peck, hen-peck

Nag: (năg), n. 1. A small horse; a pony; hence, any horse, especially one that is of inferior breeding or useless.

2. A paramour; -- in contempt. Shak.

Nag: to scold habitually; to annoy; to fret pertinaciously. “She never nagged.” J. Ingelow.

From the Writing of Ray Stedamn

I heard of a man who called his wife Peg although she really had another name. Someone asked him why he did this and he said, "Well, Peg is a short for Pegasus, and Pegasus was an immortal horse, and an immortal horse is an everlasting nag so that's why I call my wife Peg!"

I heard of a man who called his wife Peg although she really had another name. Someone asked him why he did this and he said, "Well, Peg is a short for Pegasus, and Pegasus was an immortal horse, and an immortal horse is an everlasting nag so that's why I call my wife Peg!"What is nagging, anyway? Analyze it, and it is seen frequently to be a subtle evasion on the part of the wife of her responsibility to submit to her husband.

http://www.raystedman.org/moralcon/0081.html

TERMAGANT

ter·ma·gant (tûr'mə-gənt)

n.

A quarrelsome, scolding woman; a shrew.

adj.

Shrewish; scolding.

Old Hag Syndrome

Old Hag Syndrome"Old Hag Syndrome" sometimes referred to as "Night Hag" is another commonly used term for SLEEP PARALYSIS among many different cultures mainly in the western world. The term Old Hag is probably derived from a couple of sources, one being the word for Nightmare; Night -of course, we know this already, Mare being derived from the old English term Maere meaning demon or incubus (an incubus is believed to be a demon that visits during the night). Other sources as listed by Dr. J. A. Cheyne, University of Waterloo Psych. Dept include German mar/mare, nachtmahr, Hexendrücken (witch pressing), Alpdruck (efl pressure), Czech muera, Polish zmora, Russian Kikimora, French cauchmar (trampling ogre), Greek ephialtes (one who leaps upon) and mora (the night "mare" or monster, ogre, spirit, etc.), Roman incubus (one who presses or crushes) ge, (evil spirit or the night-mare--also hegge, haegtesse, haehtisse, haegte); Old Norse mara, Old Irish mar/more.

Here is an old hag--or a stylish young woman--depending on how your eyes catch the visual representation. Word is, if you stare at it long enouch before you retire at night you'll wake in the night with a case of "Old Hag Syndrome."

Here is an old hag--or a stylish young woman--depending on how your eyes catch the visual representation. Word is, if you stare at it long enouch before you retire at night you'll wake in the night with a case of "Old Hag Syndrome."DIARY OF A MAD HOUSEWIFE

Made into a major motion picture that garnered an Oscar nomination, Diary of a Mad Housewife is a classic of women’s fiction that gave a wry voice to the nascent feminist stirrings of the 1960s and helped incite a revolution in the consciousness of a generation. After many years, this best-selling novel of Manhattan ennui is finally back in print.

Made into a major motion picture that garnered an Oscar nomination, Diary of a Mad Housewife is a classic of women’s fiction that gave a wry voice to the nascent feminist stirrings of the 1960s and helped incite a revolution in the consciousness of a generation. After many years, this best-selling novel of Manhattan ennui is finally back in print.When Bettina Balser begins to suspect that she is going mad, she starts a secret diary as a form of therapy and escape. Her fears pour onto the page: "Elevators, subways, bridges, tunnels, high places, low places, tightly enclosed spaces, boats, cars, planes, trains, crowds...." Through her observations of herself and those around her, Bettina seeks meaning in her exceedingly dreary life. Her frank examinations lead to many changes, including an extramarital fling, and her voice touches a timeless nerve, resonating on many levels— from the ever-evolving feminist consciousness to the gnawing existential search that is universal.

Diary of a Mad Housewife’s humor and insight are as alive and pertinent today as they were yesterday, and will charm and disarm men and women of any generation.

"Diatribe of a Mad Housewife" is the tenth episode of The Simpsons' fifteenth season, first aired on January 25, 2004.

Merry Wives and Others: A History of Domestic Humor Writing

by Penelope Fritzer, Bartholomew Bland

In many ways, the history of domestic humor writing is also a history of domestic life in the twentieth century. For many years, domestic humor was written primarily by females; significant contributions from male writers began as times and family structures changed. It remains timeless because of its basis on the relationships between husbands and wives, parents and children, houses and inhabitants, pets and their owners, chores and their doers, and neighbors.

This work is a historical and literary survey of humorists who wrote about home. It begins with a chapter on the social context of and attitudes toward traditional domestic roles and housewives. The following chapters, beginning with the 1920s and continuing through today, cover the different time periods and the foremost American domestic humorists, and the humor written by surrogate parents, grown children about their childhood families, husbands, and Canadian and English writers. Also covered are the differences among various writers toward traditional domestic roles—some, like Erma Bombeck and Judith Viorst, embraced them, while others, like Caryl Kristenson and Marilyn Kentz, resisted them. Common themes, such as the isolation and competitiveness of housework, home as an idealized metaphysical goal and ongoing physical challenge, and the urban, suburban, and rural life, are also explored.

About the Author

Penelope Fritzer is an associate professor at Florida Atlantic University’s Davie campus. She lives in Coral Springs. Bartholomew Bland is the director of exhibitions at the Staten Island Institute of Arts and Sciences. He lives in New York City.

HOUSEWIFE HUMORIST

Erma Bombeck

Erma BombeckErma Bombeck (1927-1996) was born in Dayton, Ohio, USA. When she was nine, her childhood home including all of the furnishings and furniture was repossessed by the bank after her father, a crane-operator, died of a stroke. To survive, Erma developed a wise-cracking, comic approach to life. At 13, she wrote her first humor column for her school newspaper.

At the age of 20 she was diagnosed with polycistic kidney disease, a hereditary disorder which causes cysts to form on the kidneys. Told that she would one day suffer kidney failure, she went on with her life—marrying, having three children, and a career as one of America’s favorite humorists.

Her column, “At Wits End,” debuted in the Kettering-Oakwood Times in 1964. She soon had a huge following in housewives around Ohio. As news of the column spread, it became a nationally syndicated column in 1965, running twice weekly in some 500 newspapers. In 1971, the family and moved to Arizona, where for three decades she wrote about being a mother, wife, journalist, and woman. Her two best known books are The Grass is Always Greener Over the Septic Tank (1976) and If Life is a Bowl of Cherries, What am I Doing in the Pits? (1978).

During the course of her career, Bombeck published more than four thousand syndicated columns in 900 papers nationwide, wrote 15 best-selling books, and became one of the world's most beloved humorist columns. She died of complications from a kidney transplant in 1996.